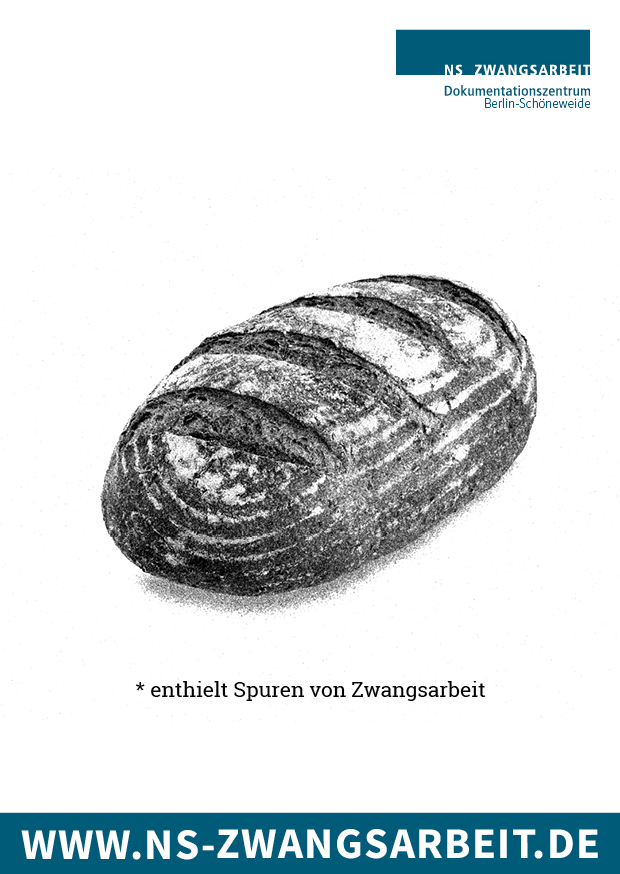

Bread - contained traces of forced labour

Bread had a fundamental meaning for forced labourers during the Second World War: it was allotted in rations, often missed, shared with each other and also stolen. Bread also determined the daily work of thousands who performed forced labour in bakeries.

In the accounts of contemporary witnesses, bread plays a central role again and again, mostly in connection with inadequate rations. Jolanta J. recalls: "And the hunger was terrible. We only got mouldy bread. Because they gave us a whole week's supply."

But bread is also present in the memories of forced labourers as a sign of mutual help. The Ukrainian Ivan S. reports about a collective accommodation in Berlin-Mitte: "But the best in the camp were [the] French. Good of soul. The best people, it seemed to us. They shared the last crumb of bread. The others didn't."

The supply of bread to the forced labourers was strictly regulated according to gender, group membership and nationality. Often the rations were meagre, as can be seen from a report by Gotthold Starke, an employee of the Foreign Office: "In the morning, half a litre of cabbage soup. At noon, at work, one litre of swede soup. In the evening, one litre of swede soup. In addition, the Eastern worker receives 300 grams of bread daily. In addition, 50-75g of margarine, 25g of meat or meat products are distributed or withheld weekly, depending on the arbitrariness of the camp leaders."

The report dates from 1943 and describes the food rations for the "Eastern workers", forced labourers from the Soviet Union. In it, Gotthold Starke denounced the inadequate food supply in the collective camps, but less out of compassion than out of concern for the security of the German Reich. The inadequate rations harboured the danger that starving workers would begin to steal, that they might revolt and turn to communist ideology.

The importance of bread for forced labourers is shown not least by the fact that baked goods were a frequently recurring photo motif during this period. As a souvenir photo or for their families at home, forced labourers took pictures of each other - in their rooms, in front of the shelters or even on excursions. It is not uncommon to find photographs of people holding whole loaves of bread in their arms.

For forced labourers, however, bread was not only an important foodstuff, but often also the object of their everyday work. In Berlin, many of the approximately 500,000 forced labourers worked in bakeries. Ten bakeries and cafés are known to have employed them in the Prenzlauer Berg district alone. Some of them even lived at the same address. Forced labour therefore happened here every day before the eyes of the neighbours.

One of these businesses was the large bakery August Wittler, which had been one of the largest bread factories in Europe since the 1920s. Thanks to mechanised production, a fully automated baking line, shelf-life processes and production specially adapted to wartime needs, the factory in Maxstraße in Wedding advanced to become a model National Socialist enterprise. In 1944, about two-thirds of the total workforce of 1,840 consisted of forced labourers, or about 1,227 people.

In addition to the production of white bread, rusks and stonemason's bread, the August Wittler bread factory baked the so-called Kommissbrot, which was particularly nutritious and durable and thus well suited for supplying soldiers. Forced labourers like the Ukrainian Ivan S., who was employed by the Wittler company, could only rave about it:

"We wanted to see the bread for the military, it should be very good. This bread should last five or six years, in water, under the ground, on the ground - it doesn't rot. In our country they gave the soldiers rusks, but here in Germany they gave them this bread. Thin slices. But our boys would sneak in and ask the German women to taste it. Black like coal. But delicious! It doesn't go rotten. And it's filling. One slice with coffee - you won't be hungry all day."

The commissary bread brought the bakery enormous success. The Wehrmacht became a major customer, and in 1936 Wittler was the exclusive supplier for the Olympic Games in Berlin.

Translated with DeepL

Numbers

About 26 million people from almost all over Europe had to work for the Nazi state in the German Reich and the occupied territories during the Second World War. Among them were prisoners of war and concentration camp inmates. The largest group was made up of the approximately 8.4 million civilian workers who were deported to the then German Reich: men, women and children from the occupied territories of Europe.

Figures on the use of forced labourers in the bakeries of the German Reich during the Second World War are not yet available, as there is no comprehensive account of this.

Present

Forced labour is by no means a long-gone injustice. According to United Nations (UN) estimates, more than 40 million people are still victims of modern forms of slavery today. 29 million are women and children. A large proportion of them are used in the food industry.

Andrew Forrest, founder of the Walk Free Foundation, which works closely with the United Nations, says: "The fact that 40 million people are still in modern slavery every day should make us blush. Modern slavery affects children, women and men worldwide. This documents the profound discrimination and inequality in the world, coupled with a shocking tolerance for exploitation. We must stop this. We can all help change this reality - in business, government, civil society and as individuals."